In 1991-2, I was teaching a first year printmaking class, eventually getting to intaglio in February. When I asked the students to purchase a sheet of zinc from the bookstore, a girl came to me very upset as she could not afford the metal at this time of the school year. Was there some cheaper metal that could be used instead? I thought of iron and aluminum, but felt the latter would come with a smoother surface and require little polishing before applying the hardground. Besides I didn’t like the farther use of nitric acid for iron, so chose aluminum for the small editions required in my class. When I suggested the change to the department head, he rejected the use of ferric chloride, one of the possible mordants other etchers had used. While stannous chloride was a possible alternative, it was hard to get and very expensive when the charges for shipping dangerous materials was added.

A few years earlier, while I was demonstrating my toner process for use with positive lithographic plates, the master’s student, Christine Christos had become interested to see if the technique could be used on intaglio photo plates as well. While she succeeded to expose and etch a zinc plate, I became interested in getting nitric acid out of the classroom, so started to work on using electric current to remove metal. We worked together and eventually published an article in Leonardo, Vol. 26. #4, 1991. This technique was now available for our students with the power supply unit I assembled for the department, but only a few students chose to use it, even though it could etch any hard metal for very large editions. It worked well on aluminum, but having only one power supply unit for a large class, did not allow many etchings to be made in any given period, so another method had to be found.

Years earlier, as a lithographer who wanted a better ink base on aluminum plates, I tried a formula used by platemakers for deep etch plates in the offset printing industry. Its’ major active chemical was cuprous chloride (which I didn’t have) along with hydrochloric acid; so hopefully I tried copper sulfate and the acid to see if it might work. When I tried the solution, there was no copper plating on the aluminum surface, but corrosion where the liquid was applied. After a few varied attempts, I gave up the idea, but this unsuccessful research had stayed in my mind. Was it possible to use this chemical reaction to produce good images on aluminum, I asked myself?

I had some thicker aluminum at home that was used on other projects, so I immediately started to do research with copper sulfate as a mordant. I was able to get good results to find it worked well on aluminum and zinc, so I started to experiment its use in the class - with one bath for both metals.

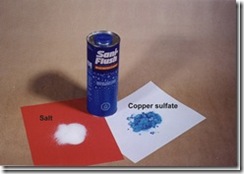

In the spring of 1992, the university hosted an international conference “New Directions in Printmaking; the technical sideâ€, in which new safer techniques were featured. As the etching mordant was not fully developed, we only had the bath in the print studio with information about it for those who were interested; but not put into the official program. I recall discussing the technique with a number of etchers who where fascinated in the blue solution. Later I discovered that the bath corroded both metals by just adding common salt instead of hydrochloric acid, so introduce that process into teaching the summer session class that year. I soon found that the acid had kept the formation of aluminum hydroxide at bay, which forms a gel-like solution that makes the bath unsightly and reduced it effectiveness. What was needed is an acid that would not interact with the aluminum, just constantly removing alkalinity so the hydroxide would not form. While either sulfuric or nitric acids would work with oxygen in their composition, I did not want to use dangerous acids if possible. The answer was sodium bisulfate; a weak form of sulfurous acid that I was accustomed to using in my goldsmithing practice. Since this material was harder to acquire, a cheaper and perfect alternative turned out to be Sani-Flush, available in grocery stores across North America; used as a toilet bowl cleaner.

In the spring of 1992, the university hosted an international conference “New Directions in Printmaking; the technical sideâ€, in which new safer techniques were featured. As the etching mordant was not fully developed, we only had the bath in the print studio with information about it for those who were interested; but not put into the official program. I recall discussing the technique with a number of etchers who where fascinated in the blue solution. Later I discovered that the bath corroded both metals by just adding common salt instead of hydrochloric acid, so introduce that process into teaching the summer session class that year. I soon found that the acid had kept the formation of aluminum hydroxide at bay, which forms a gel-like solution that makes the bath unsightly and reduced it effectiveness. What was needed is an acid that would not interact with the aluminum, just constantly removing alkalinity so the hydroxide would not form. While either sulfuric or nitric acids would work with oxygen in their composition, I did not want to use dangerous acids if possible. The answer was sodium bisulfate; a weak form of sulfurous acid that I was accustomed to using in my goldsmithing practice. Since this material was harder to acquire, a cheaper and perfect alternative turned out to be Sani-Flush, available in grocery stores across North America; used as a toilet bowl cleaner.

Recently, while looking through my research notes for another reason, I ran across the work I was doing to see how much aluminum would be removed for a given weight of copper sulfate. These tests are dated November 12 and 13th, 1992, not quite a year after my first experiments. I had just retired from faculty, but appointed as artist-in-residence; still having access to the resources at the university. Because the process was working so well, I decided to submit a paper to LEONARDO, the international refereed journal in the arts; where I already had other articles published. To better appreciate the chemical reaction, which was now beyond my basic understanding of chemistry, I contacted the department of chemistry for their help. Dr. Bader accepted the challenge, along with some other professors, who in turn involved their students in the project. The students were asked to figure out exactly what was happening and try to explain it to their professors; then give me an explanation as well. From Dr. Baders’ and the students account, I put together the article that was submitted to the editor of LEONARDO in April 5, 1994.

I told the editors that the article was already being distributed by mail as I had Xerox copied my papers for universities across the continent, sending it along with other printmaking information. Printmakers in other countries were now also in contact with me by e-mail, seeking information on the toner and waterless process I had developed earlier. I can’t remember exactly when I put up my website on the university server, but that reduced the cost of copying and mailing large bundles of paper. As the copper sulfate mordant became better known with this move, I started to get more inquires for that process than the others I had developed. To this day the copper sulfate mordant paper on my university website gets the most attention.

The article was accepted by the referees, but I was informed by the editor that there were now some concerns within the LEONARDO office in San Francisco, where copper sulfate was the cause of pollution problems in the bay area from the wine growing valleys nearby. I explained that there was no reason for anymore copper being released into the water than from etchers using nitric acid on their copper plates, or even the copper pipes used for plumbing. Probably even less; if care was taken in handling materials. A second set of referees where chosen and the review process started again. Finally the article was published in LEONARDO, Vol. 31, #2, 1998.

Because etching is not my major printmaking media, I have done much less work with it after my initial research. In my later summer session classes, I started to use larger amount of salt to produce copper chloride, which was much more active than suggested in my first publication. Now I called for enough salt to be added until the solution turned green. I also discovered in my own research at home, that this solution would redissolve the free fine copper particles produced during etching, when left overnight. While this process could not likely go on indefinitely, it could continue a long time if the aluminum hydroxide could be removed as it settled in a resting container. The university has installed a large plastic barrel with a spigot a bit off the bottom, so that the alumina could settle, allowing the reclaimed green mordant to be put back into service.

Because etching is not my major printmaking media, I have done much less work with it after my initial research. In my later summer session classes, I started to use larger amount of salt to produce copper chloride, which was much more active than suggested in my first publication. Now I called for enough salt to be added until the solution turned green. I also discovered in my own research at home, that this solution would redissolve the free fine copper particles produced during etching, when left overnight. While this process could not likely go on indefinitely, it could continue a long time if the aluminum hydroxide could be removed as it settled in a resting container. The university has installed a large plastic barrel with a spigot a bit off the bottom, so that the alumina could settle, allowing the reclaimed green mordant to be put back into service.

Because of the price of zinc plates, they are seldom if ever used by our students, as large sheets of aluminum are precut into 24 x 32 inch sizes for sale to them at a fraction cost of zinc. Unlike the zinc and acid etchings, the size of the printed images has greatly increased, demanding a special tray just for the very large plates being used by some of the students. The characteristic of aluminum is the crystalline structure within the metal, which is revealed by the copper sulfates action. This means there is no need for aquatinting to get solid color or lighter tints of any hue. In our etching trays, we have plastic grill work, coming from discarded fluorescent lights, which is raised off the tray bottom to allow any sediment to rest below undisturbed.

Action of copper sulfate on crystalline structure of aluminum

I have presented the process at a SGC conference and included it when ever I was asked to give workshops at universities across North America on my other innovations. Copper sulfate has become very popular in Europe for etching zinc under the name of Bordeaux and Saline etches. It is considered to be much safer on zinc than ferric chloride, which can produce chlorine gas as it is very reactive with that metal.

When I started to do my research into using copper sulfate, I had no idea that Goya might have used it in some of his zinc etchings. This only became known to me by what Cedric Green had said about Bordeaux etch, after I became aware of his website. I wonder how many times the wheel has be reinvented?

Anyone wanting more technical information on this process, you can find it on the University of Saskatchewan website at: http://homepage.usask.ca/~nis715/.

Nik Semenoff